The vine as a cultural spectacle: evolution of its representation throughout history

If the presence of the vine has been attested for thousands of years, it was not until the modern era that it was “seen” (and therefore represented) as the constituent element of a cultural landscape. As Yves Leginbühl reminds us, “if the term landscape was born in the West during the Renaissance, there were undoubtedly wine-growing landscapes well before this period.”

© Aurélien Terrade

The vine: a contemporary invention

Since Antiquity, the vine has been represented as a symbol, as a setting or as an allegory, then in realistic scenes before becoming a subject of landscape offering itself to the viewer. This recent discovery of the cultural character of the vineyard landscape is comparable to that of seascapes or mountain landscapes by the Romantics in the 19th century. It is at the end of this century that begins a recognition of the vineyard landscape. The vine that artists of antiquity show on paintings, sculptures, ceramics, mosaics has a symbolic function. It is linked to the cult of the dead or represented as an attribute of the god. When it is not represented for its sacred character, it is an element of decoration, the two functions are often mixed.

Adolescent Bacchus, Caravaggio, ca. 1600, Uffizi Museum, Florence.

In classical times, it is still in mythology that we find representations of the vine.

In Egypt, the painters who show in several tombs all the details of the harvest of a vine, led on high pergolas, give a representation as faithful as possible but in a symbolic purpose.

In the Middle Ages, the vine remained intimately linked to the sacred. It appears essentially in religious scenes. Although they belonged to a feudal society that was mostly rural, artists did not “see” the vineyard landscape. The vine, always carrying a strong symbolic value, remains reserved for the illustration of various episodes of the Bible and the months of the calendar: pruning in March, harvest in September. These symbolic rituals of the vineyard are not, however, devoid of realism. In the harvest scenes, we see the winegrower performing ancestral gestures, delicately supporting the grape with one hand and preparing, with the other, to cut the stem before placing it in a basket.

The 15th century marked a turning point in man’s apprehension of the world; it desacralized it and the mistrust towards the sensible world, instituted until then by Christianity, gave way to a new curiosity, to a desire to discover the natural framework of human life.

If the vine does not appear in the first landscapes, which are mostly imaginary, it appears in a much more realistic form in the illuminations of religious works (breviary calendars) or secular works (hygiene books or treatises on agronomy). One of the most eloquent examples is given to us at the beginning of the 15th century by the miniatures of the Limbourg brothers which illustrate the calendar of the book of hours of the Duke of Berry.

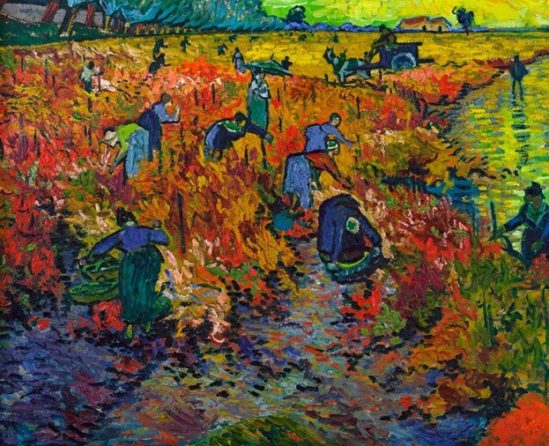

The Red Vines of Arles, Vincent Van Gogh, Pushkin Museum, Moscow.

Although it is still a harvest scene, Van Gogh with the title of this painting gives more importance to the landscape than to the characters

These “Very Rich Hours” obey the medieval stereotype that favors the representation of seasonal work, the most visible form of the passage of time, for a predominantly rural society. In the vineyards located at the foot of the castles of Saumur and Lusignan, very realistic scenes take place which inform us about the work of the vine in the late Middle Ages. These small landscape paintings, far from their religious purpose and witnessing a new interest in nature, can be called “proto-wine landscapes”. During the Renaissance and the Classical period, as in Antiquity, the vine was once again associated with Dionysus/Bacchus and his procession, an opportunity to paint wreaths of grapevines with the precision of a still life. In the 19th century, the vineyard of painters, the first reporters-lithographers and photographers is almost always the frame of a realistic scene, the space where the rural work is accomplished and praised in the painting. It is the winegrower who is in the spotlight, not the vineyard landscape. The pictures of the 19th century show above all the man in the vineyard. The same is true of travel books: tourism is developing, but travelers are mostly interested in landscapes full of history and embellished with ancient monuments. A few paintings are however an exception, in particular Van Gogh’s The Red Vines of Arles, a harvest scene where the vineyard plays a major role.

At the end of the 19th century, the vineyards replanted after the phylloxera crisis changed their appearance. The vine planted in rows, trellised, becomes the majority and structures differently the places it occupies by radically modifying the visual effect it produces.

Photography allows a new look at the landscape. In 1888, the Kodak instant camera n°1 developed by Georges Eastman, by offering a new freedom to photographers, changed the way of seeing the world. But the imitation of nature is no longer the issue of modern painting. Photographers were more interested in the winegrowing society than in the winegrowing landscape.

Amour vendangeur, fragment d’une mosaïque tunisienne du IVe siècle, musée du Louvre, Paris.

Les Romains sont sensibles à l’aspect décoratif de la vigne

It was not until the end of the 20th century that the concept of the vineyard landscape was imposed by a new cultural approach to wine. Already, since the creation of IGs, wine had begun to change its status, leaving the domain of food to integrate that of the art of living. The first issues of the Revue du Vin de France were published in 1927, those of Cuisine et Vins de France in 1933. Hugh Johnson’s famous World Wine Atlas, published in 1971, introduced the world to the specificity of wine-growing regions. Tasting wine became a cultural process. From drinking to seeing, there is only one step that wine lovers took in the 1980s with visits to estates and wineries; the Châteaux Bordeaux exhibition was presented at the Georges Pompidou Center in 1989, and Les paysages de la vigne was selected to celebrate the second millennium.

© Serge DETALLE

Since 1992, wine sites have been included on the Unesco World Heritage List. This international organization has given itself, among other things, the objective of reducing the rate of impoverishment of biological diversity, specifying that the natural links that exist between biological diversity and cultural diversity represent a source of exchange, creativity and innovation that favors sustainable development. Indeed, in the 21st century, the criteria for wine appreciation have evolved.

From now on, they integrate the respect of the environment. If the creators of the landscape, the winegrowers, take this into account, the spectacle of the vineyard should continue to attract a large public.